Obesity and Pregnancy: Risks, Care and Prevention

Obesity in Pregnancy: Risks, Care, and Prevention

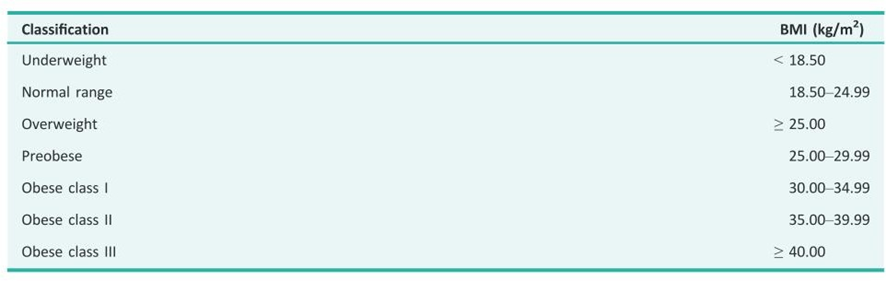

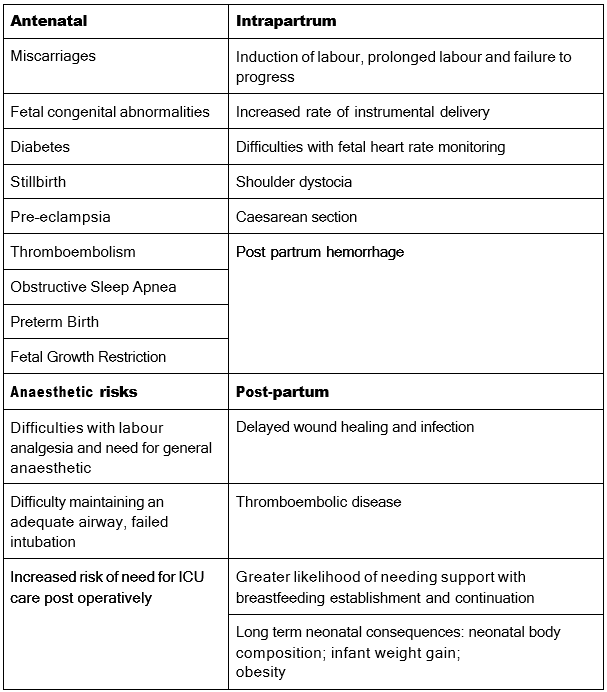

Rates of women with a body mass index (BMI) greater than 30 of the reproductive age are rising , with recent estimates over 25% common in many countries. Therefore obesity in pregnancy is a significant health issue. Obstetricians, when meeting an obese woman in early pregnancy, often focus on the short-term complications of obesity in pregnancy, such as the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), pre-eclampsia and thrombo-embolism, the difficulty of fetal assessment, using ultrasound and fetal heart rate (FHR) monitoring, and the risks of labour. These complications often increase with increasing BMI in a dose-response fashion.

Complications need to be considered seriously, as the potential problems may not be minor: obesity has been shown to increase the risk of morbidity and mortality. While the immediate risks may be evident to any clinician in practice, what may not be appreciated are the subtle risks of obesity in pregnancy, how even mild obesity may affect progress in labour, the relative malnutrition of vitamins and minerals, maternal malabsorption and effects of maternal obesity on both fetal programming and long term risk of cardiovascular disease and the increased risk of childhood obesity.

In addition, though many appreciate the risks of morbid obesity (BMI >40, class 3 obesity) on pregnancy, the clinical team may not fully appreciate the risks of even mild obesity on pregnancy and the effect of pregnancy on the associated complications of obesity Adipose tissue is an endocrine organ, synthesizing and secreting a variety of hormones and inflammatory markers, including cytokines, leptin and adiponectin. These adipocytokines can have profound effects on pregnancy.

The adverse impact of obesity on pregnancy begins prior to conception and continues throughout pregnancy and into future generations. Obesity reduces fertility and has been shown to affect the health of the human oocyte and the quality and development of the embryo early in gestation. Once pregnant, almost all complications are more common and the increased likelihood of serious side-effects shows a direct relationship with the class of obesity. It is important to recognise that the increased risk of stillbirth is significant even for Class 1 women with obesity.

Furthermore, evidence clearly demonstrates prenatal and lactational maternal obesity is associated with cardiometabolic morbidity and neurodevelopmental disorders in offspring. Many women are unaware of current recommendations surrounding gestational weight management and the effect of significant antepartum weight gain on the current pregnancy. Women may have difficulty losing the additional weight gained in pregnancy, which increases the risk for future pregnancies.

Preconceptional care

Identifying and addressing obesity before and between pregnancies

During pre-conception visits, primary and maternity healthcare providers should record a woman’s height and weight. They should also discuss ways to improve nutrition, physical activity, and weight prior to becoming pregnant. If obesity is present, clinicians should explain how excess weight can affect fertility and increase the risk of complications during pregnancy.

Nutritional supplements

Women with obesity who are planning a pregnancy should be advised to take a supplement that includes folic acid and 150 μg of iodine before conception. A higher folic acid dose (5 mg) is recommended for those with a BMI over 30, as their risk of neural tube defects is elevated.

Psychosocial factors

Depression is a well-recognized contributor to weight gain and obesity. If depressive symptoms are identified, appropriate psychological support and referral should be offered before pregnancy, with continued assessment and referral once the woman becomes pregnant.

Antenatal care

Recording BMI

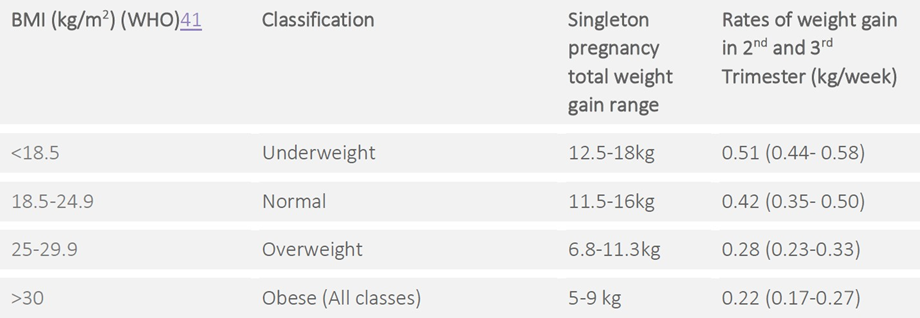

At the first antenatal visit—preferably before 10–12 weeks—every pregnant woman should have her height, weight, and BMI measured and documented. Weight gain should be tracked by weighing the woman at least once each trimester.

Counselling on pregnancy risks

Pregnant women with obesity should receive tailored guidance about the increased risks linked to obesity in pregnancy and the strategies planned to reduce those risks.

Nutritional supplementation

Women with obesity should be advised to take 5 mg folic acid and 150 mcg iodine daily. They also have a higher likelihood of iron and vitamin D deficiencies. Referral to a dietitian is recommended for individualized nutritional advice and guidance on appropriate weight gain during pregnancy.

Antenatal screening

Women with obesity should be offered early diabetes screening and informed that non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) carries a higher chance of returning ‘no result.’

Glucose tolerance testing for gestational diabetes

Early GTT should be offered, with a repeat test at 28 weeks if the initial screening is normal.

Anaesthetic evaluation

If indicated, women with obesity—particularly those with a BMI over 40—should be referred for an antenatal anaesthetic assessment.

Pre-eclampsia prevention

Calcium and aspirin supplementation may be considered from early pregnancy until 36 weeks when other risk factors are present.

Ultrasound and fetal growth monitoring

Women with obesity should be offered additional serial ultrasounds to monitor fetal growth, with timing determined by the overall clinical situation. Obesity increases the risk of congenital anomalies, growth restriction, and macrosomia. However, ultrasound imaging in the second-trimester anatomy scan is less sensitive in women with obesity, resulting in lower detection rates of structural abnormalities.

Timing of birth

There is no clear universal recommendation for the ideal timing of birth in women with obesity who have no other medical issues. Waiting for spontaneous labour beyond the due date may raise the risk of macrosomia and stillbirth. Induction of labour does not seem to increase caesarean rates, and its benefits grow with higher BMI. For women with a BMI over 50, delivery by 39 weeks should be considered due to significantly increased stillbirth risk after this gestation.

Mode of birth

Women with obesity—especially those with Class III obesity—should be informed about their increased likelihood of requiring an emergency caesarean section.

Intrapartum and postpartum care

● Intrapartum risks linked to obesity should be managed through standard safety measures, including readiness for postpartum haemorrhage and shoulder dystocia. Because women with obesity have a higher risk of thromboembolism, it is important to ensure good hydration, promote early mobilization, and provide individualized care.

● As obesity is associated with reduced initiation and continuation of breastfeeding, women with obesity should receive support both during pregnancy and immediately after birth to help them begin and sustain breastfeeding.

● Postnatally, women with obesity should continue to receive guidance on nutrition and physical activity from qualified professionals, with the goal of promoting healthy weight loss. This period may also provide a useful opportunity to investigate potential underlying contributors to obesity, such as thyroid or cortisol abnormalities.